When Good Ratings Meet Real Scoring

Written by Thomas Nilsson - In the first article, “When Averages Stop Being Fair,” I explored why a single rating number can never fully describe how a boat behaves across all conditions. Boats are not constant machines; they respond differently to wind strength, wind angle, and course geometry.

That naturally leads to the next question: Once we have a rating that represents the reality of the racing conditions, how do we actually use it to score a race?

This is where theory finally meets practice.

One Rating – Many Ways to Use It

One of the most common misunderstandings around ORC is what we mean by “the rating.”

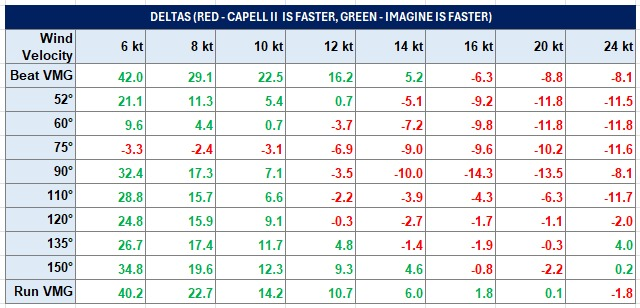

The rating is often reduced in everyday conversation to a single number — APH, CDL, or similar. But in reality, the ORC rating is a matrix of time allowances, covering different wind strengths and wind angles. That full matrix is what the VPP produces.

The winner of a race is therefore not decided by “the rating alone,” but by how the rating is applied through a chosen scoring method.

Most sailors, however, first encounter ORC through Single Number scoring, and that is where we begin.

The Foundation: Single Number Scoring

Single Number scoring has widespread acceptance and use in ORC racing worldwide. It is stable, predictable, and easy to administer, and is often used as a handy tool for making class breaks, which is precisely why it is so widely used.

A Single Number assumes an average race sailed in an average mix of conditions. On an ORC certificate, these values are typically provided for two standard course models:

- Windward/Leeward (WL):

A simplified course consisting of 50% upwind and 50% downwind sailing.

- All Purpose Handicap (APH):

A hypothetical circular course sailed around an island that represents an even distribution of all wind angles across a Gaussian distribution of wind speeds centered at 12 knots.

For many club races and series, this abstraction works surprisingly well. But its limitations become visible as soon as real-world conditions move away from the “average.”

Why Identical Single Numbers Can Behave Very Differently

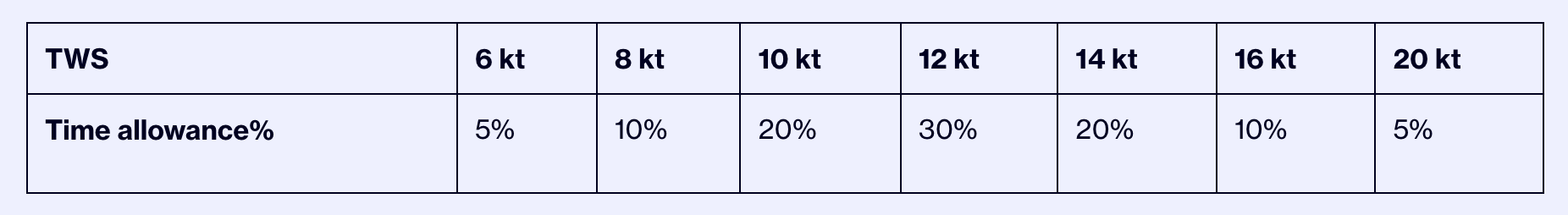

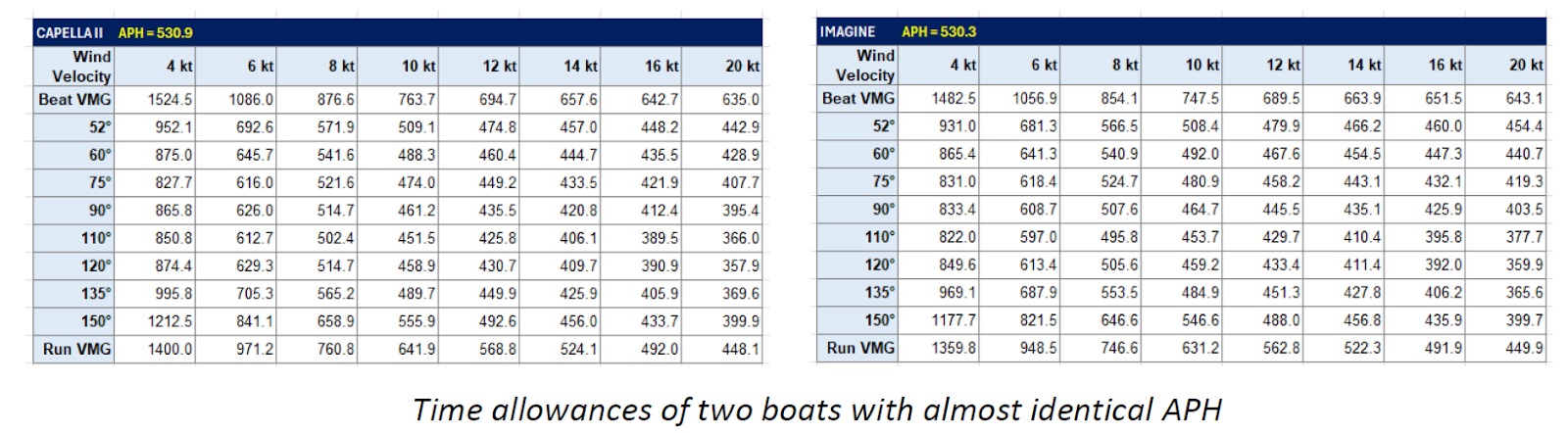

A useful illustration is when two boats have nearly identical APH values.

On paper, they appear equal. But when we look deeper — across different wind strengths and angles — a very different picture emerges.

In the rating matrix, one boat may be consistently faster upwind in light air, while the other gains significantly on reaches or downwind as the wind builds. The average hides these characteristics.

This is why a Single Number is not wrong — it is simply incomplete.

And this is exactly where scoring choices begin to matter.

Time-on-Time and Time-on-Distance: Asking Different Questions

Once a Single Number has been selected, race organisers must decide how to apply it. This is where Time-on-Time (ToT) and Time-on-Distance (ToD) come into play.

Although they often produce similar results, they reward different types of performance.

Time-on-Distance (ToD): Speed Over Distance

Time-on-Distance normalises performance over the sailed distance.

Corrected time is calculated as: Corrected Time = Elapsed Time – (ToDΔ × Distance)

Where the ToDΔ is the difference between a boat’s ToD value and that of the fastest boat in the fleet.

Key characteristics of ToD:

- The handicap is expressed in seconds per nautical mile

- The time allowance does not change with wind velocity

- The allowance does scale with course length

- It is very easy for competitors to calculate how much time they need to beat another boat

ToD works best when:

- The course is compact

- Wind conditions are relatively stable

- All boats experience similar conditions

It emphasizes raw speed differences.

Time-on-Time (ToT): Efficiency Over Time

Time-on-Time applies the handicap directly to elapsed time: Corrected Time = Elapsed Time × ToT

The ToT coefficient is derived from ToD:

ToT = 600 / ToD

Key characteristics of ToT:

- Course distance does not need to be measured

- Time allowance increases with race duration

- It is generally more forgiving when fleets spread out

- It tends to be fairer when conditions evolve during the race

ToT is often preferred for:

- Coastal races

- Offshore legs

- Venues with current

- Races where wind changes significantly over time

- When local convention prefers this style over ToD

Same Rating, Different Outcomes

What becomes clear is that ToT and ToD are not competing philosophies.

They are tools.

Choosing between them is an active decision about which type of fairness a race organizer wants to prioritize:

- Speed over distance, or

- Efficiency over time

Neither choice is universally “right” or “wrong.”

From Averages Toward Conditions

Single Number scoring — whether applied through ToT or ToD — still relies on averages. It assumes that the race sailed resembles the theoretical model behind the number.

As long as this assumption holds, the results are robust.

But modern racing increasingly challenges this assumption.

Courses now include long reaching legs, asymmetric layouts, transitions between wind strengths, and mixed offshore/coastal formats. In these cases, asking an average number to represent reality becomes increasingly problematic.

ORC therefore does not stop at Single Numbers.

The system already contains tools that apply the rating matrix more directly — across wind ranges, wind angles, and course geometry — acknowledging that boats behave differently depending on conditions.

Those tools deserve their own discussion.

Fairness Is a Choice, Not a Constant

The key takeaway is simple:

Scoring is not a neutral afterthought. It is a choice.

Single Numbers, ToT, and ToD are not compromises — they are practical solutions for situations where conditions cannot be fully captured.

Understanding when an average is “good enough” is now just as important as understanding how ratings are calculated.

A Note on Order — and Why This Series Runs Backwards

From a purely technical perspective, there is a strong argument that this article series should have been written in the opposite order.

Logically, one could start by explaining course- and condition-based scoring first — because that is where the full ORC rating matrix is actually used as intended. From there, Single Number scoring would naturally appear as a simplification, applied when conditions cannot be described with sufficient precision.

That approach would reflect the system as it is designed.

However, this series deliberately takes the opposite path.

Most sailors encounter ORC through Single Numbers first. APH, CDL, and similar values are what people see on certificates, discuss on the dock, and use when planning races. That mental model is deeply ingrained, even though it does not capture the system's full logic.

By starting where sailors think ORC begins, and then gradually revealing why that intuition is incomplete, the aim is not to challenge sailors, but to bring them along.

In the next article, I will therefore complete the circle by looking at PCS Constructed Course and Weather Routing Scoring — not as “advanced options,” but as the methods that most directly reflect how ORC was always meant to be used.

Leer en Español

Leer en Español